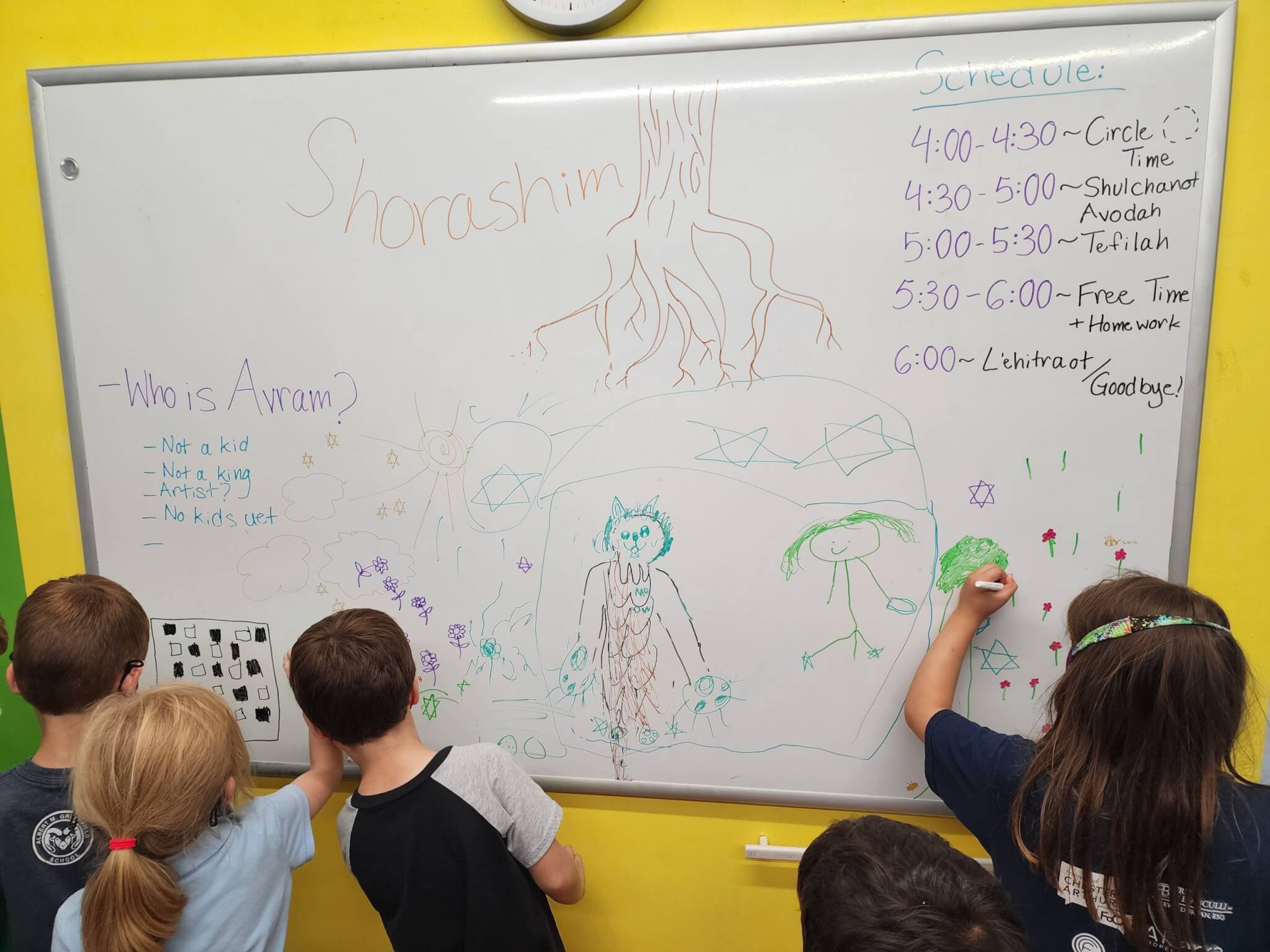

Every educator has a different reason for being passionate about working with children. However, the core of that drive is almost always the kids themselves. In my case, I am drawn to this work because I’ve always found that there are many days where I am not the one teaching. In many instances, the kids teach me and open my eyes to new revelations. This is undoubtedly true for my Shorashim (1st-2nd grade) kvutzah (group) in our Center City Makom Community Lab School.

Whether we’re discussing the story of Yitzchak and Rivka or defining holiness, I can always count on the kids in Shorashim to pose questions that challenge each other as well as my own thinking. During our unit on Avot V’ Imahot, we discussed the story of Avraham sending Eliezer to find a wife for Yitzchak. Throughout this unit, we dissected text through the lens of reflecting on our ancestors. Each day, we asked ourselves: What can we learn from those who came before us? What traditions do we want to maintain and what choices of theirs do we want to improve upon? In our textploration, we came across the line:

Once he arrived, Eliezer made the camels kneel down by the well outside the city, at evening time, the time when women come out to draw water. (Genesis 24:11)

Suddenly, the kids were in uproar. They were full of questions: “Why did the women have to collect water? Did they have a choice? Why were certain people expected to do certain jobs? What about the [nonbinary people]?” They were astounded by the lack of choice and personal autonomy given to individuals during ancient times. This sent us into a whirlwind discourse around traditional gender roles and their relevance today. By the end of this discussion, the Shorashim were unanimously chanting that everyone should “AT LEAST” get a choice. I irrefutably agreed. This was not a course of discussion that we’d included in our lesson plan but as soon as the learners began to delve into the complexities of this topic, it was apparent that we needed to pivot from the dialogue we’d intended to facilitate. Their observations and perspectives needed space to be explored, and we were happy to accommodate that.

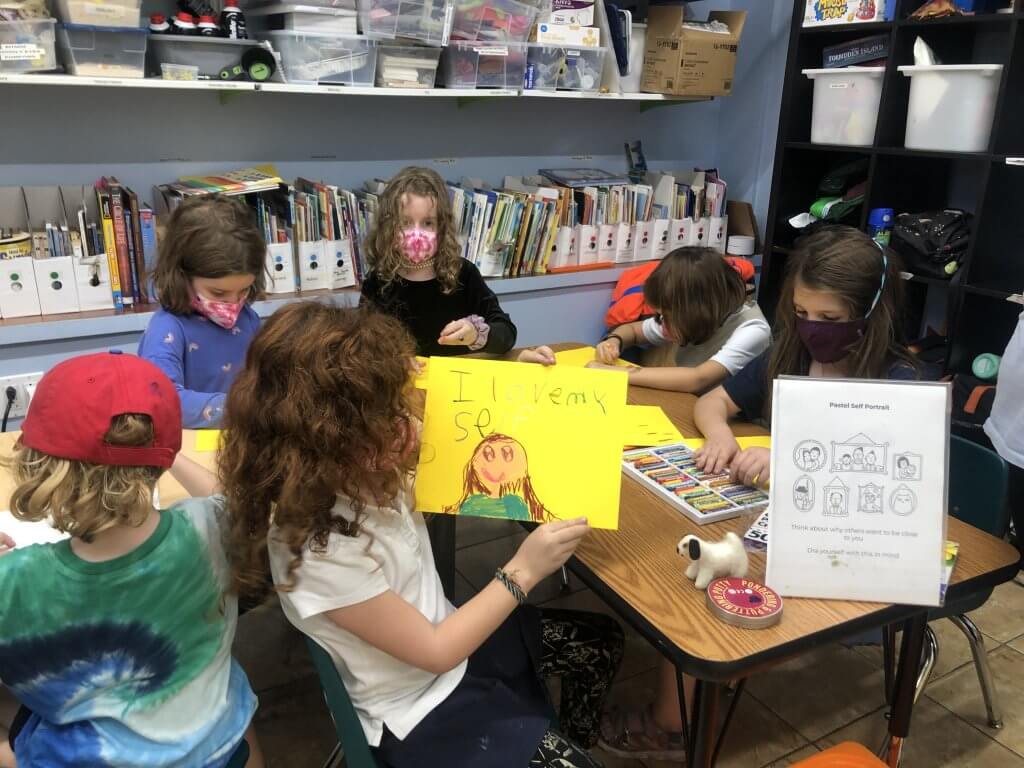

Holiness is an enigma of a concept. As a grownup, I have a very difficult time defining it ,and I’m sure I’m not alone in that. As we began our next unit on praise, we determined that it was vital for the kiddos to understand holiness in order to do the unit justice. I asked the Shorashim “What does it mean to be holy? What is a holy person like?” They proposed some interesting interpretations that I hadn’t yet considered. However, what I found most interesting about their responses was the duality within them. They said a holy person is “famous” but that a holy person can also be “unknown”. Similarly, they said that a holy person is “giving and generous” but that people who have nothing to give can also be incredibly holy. We determined based on everyone’s perspectives that the overarching trait that unites all holy people is positive intention.

I love that I never know quite what to expect from my kvutzah when I begin textploration. More often than not, their thoughts and questions steer us in an entirely different direction than I originally planned for our lessons. Seeing the way their minds work and witnessing their world views evolve is humbling and eye-opening. I look forward to continuing to learn from them and their interpretations of our shared Jewish wisdom as well as the world at large. It reminds me why I became an educator and that none of us are ever truly finished learning.