What happens when we jump to conclusions and judge a situation before we get all the details? The text of Migdal Bavel (the Tower of Babel) says that God came down to see the tower that the people were building (Genesis 11:5). Rashi wonders why. Didn’t God already know what was going on without coming down to look? Rashi suggests that the text “intends to teach the judges that they should not proclaim a defendant guilty before they have seen the case and thoroughly understand the matter in question” (Rashi on Genesis 11:5). Here’s the mock trial project we did to play with that lesson.

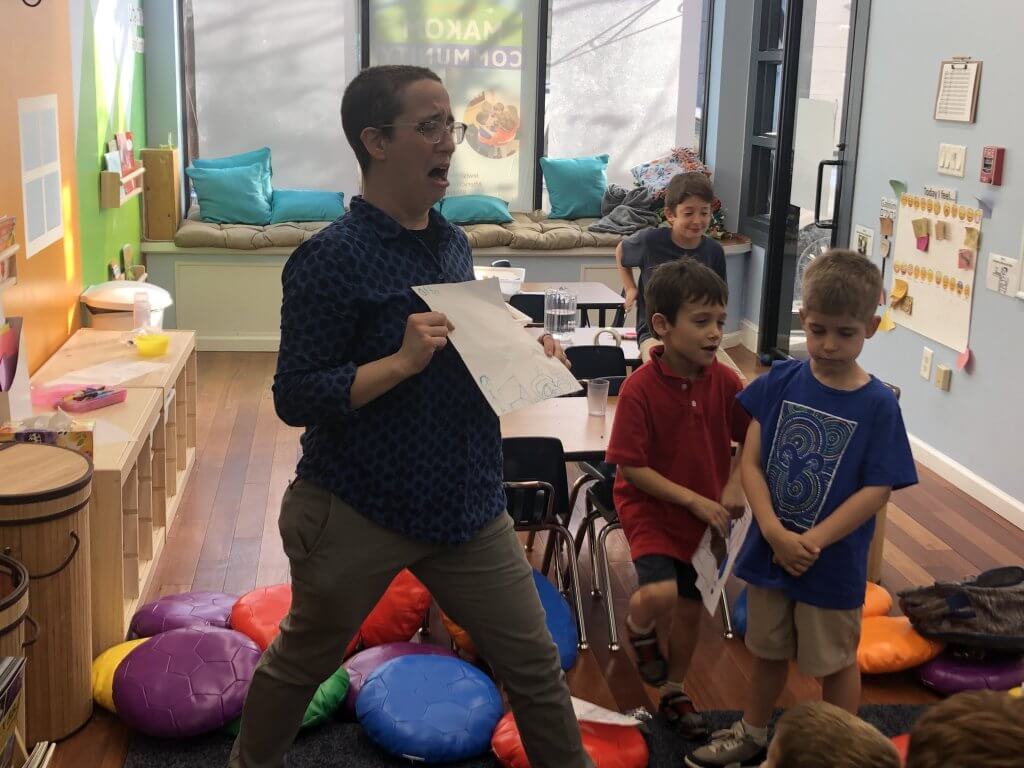

We divided the kiddos into four groups. Each group had information for one side of one of two stories. In the first scenario, a kid was accusing their friend of scribbling all over the picture they were drawing. In the second scenario, a kid was accusing their friend of throwing their backpack and knocking down the block tower creation that the first kid was building. In the small groups, our learners took the information they had and created evidence (eg: the picture covered in scribbles; the offending backpack) and witness testimonies (eg: a teacher who observed the drawing kiddos; a friend who interacted with the backpack thrower shortly before the incident).

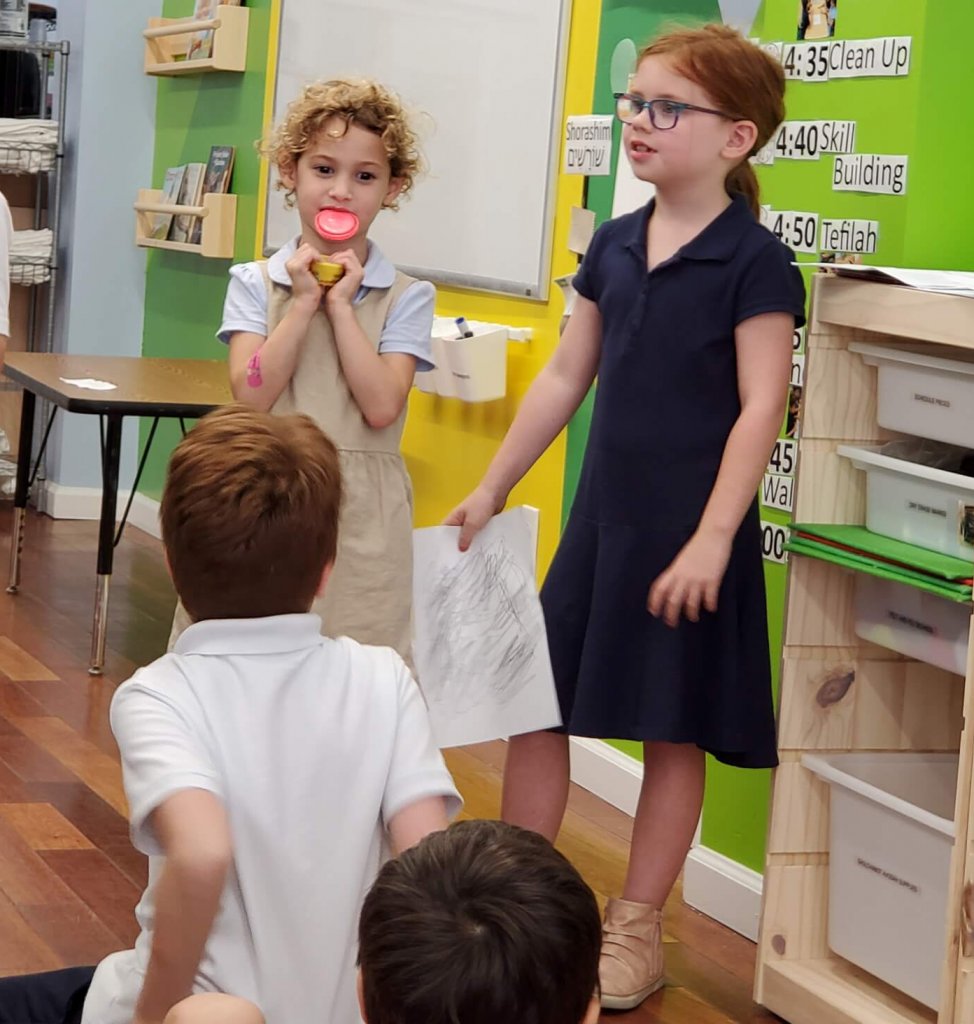

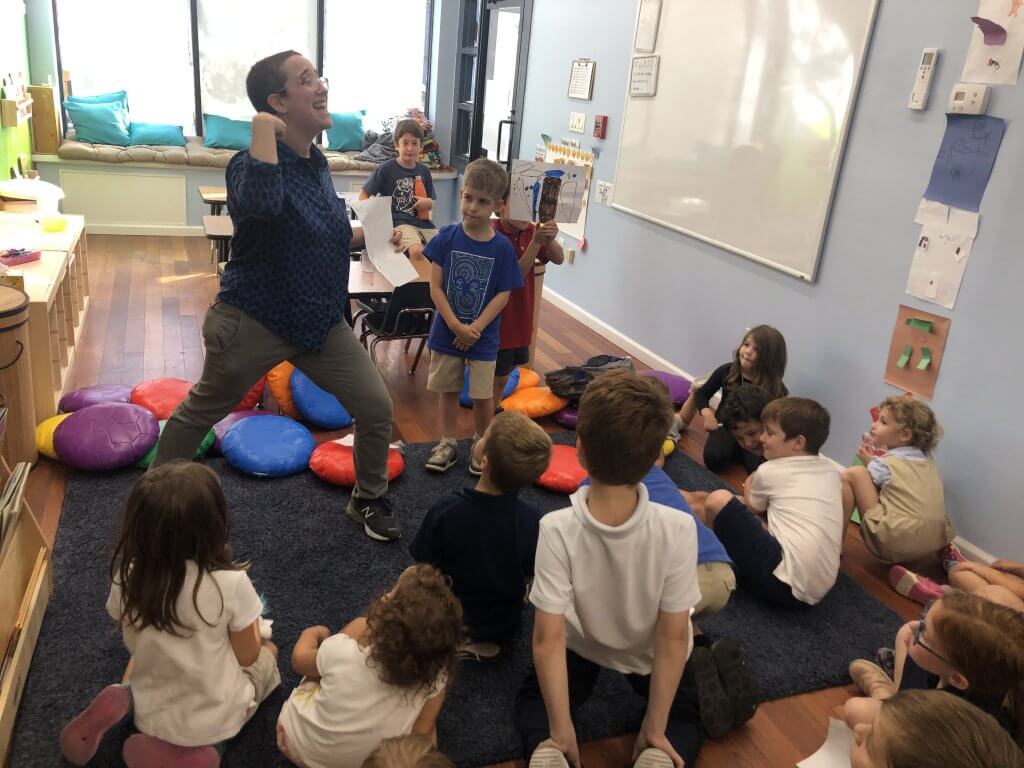

One side of the scribbling scenario presented their case. “One day,” a third grader recounted, “a boy and a girl were sitting together coloring nicely. When suddenly, someone walked by and scribbled all over their papers!” Another student dramatically flourished the ruined artwork as evidence. Then we asked for the audience, our de facto jury, to reflect: Who was responsible for the scribbles on the paper? Unanimous vote for the kid who walked by and just scribbled. What should we do to repair the situation?

- Start drawing again.

- Turn the papers over.

- Install security cameras so no one will scribble on papers anymore.

Then the other side of the same scenario presented their case. It turned out that both kids were drawing next to each other, and each of them drew on the other’s paper. The kid accused of scribbling proclaimed that the other kid started it — she only scribbled in self-defense! The jury reflected again: Do we think someone different was responsible for the scribbling now? Some votes for one kid, some votes for the other; lots of votes for both. It turned out that the situation was more complicated and ambiguous when we fully “[saw] the case and [understood] the matter in question.”

We experimented again with the blocks scenario. Initially, the conclusion was clear. Those poor children were happily building until someone chose to throw their backpack and ruin everything! Clearly the backpack-thrower is guilty. How do we fix it?

- Never throw backpacks.

- Check in before smashing someone else’s creation.

- Build your own creation if you want to crash it.

But then the final group presented their case. Apparently, the kid who threw their backpack was having a truly awful day – fight with a friend, scraped knee, homework dunked in a puddle. On top of that, the kids building blocks were set up right in front of the cubbies! The backpack hit the blocks totally by mistake; the frustrated thrower was just aiming for their cubby. So now: who is responsible for the block tower breaking? Some votes for the block builders – don’t build in front of the cubbies! Some votes for the backpack thrower – no matter how frustrated we are, throwing things is still never OK.

Judging a situation is tricky business! Getting a full picture of what happened often leads to a more ambiguous understandinding of who was at fault or how to respond. One important lesson I’m going to take from our mock trials is how not a single kid suggested any form of punishment to repair the mistakes made in their scenarios. They saw that getting a fuller understanding allows us to extend our compassion – maybe another person needs some extra kindness and we didn’t realize before; maybe there’s a secondary problem that needs to be discussed. On Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) we have a chance to judge how well we managed to be the best versions of ourselves in the previous year. Let’s remember to appreciate all the details of our situation and to judge ourselves with compassion and kindness.