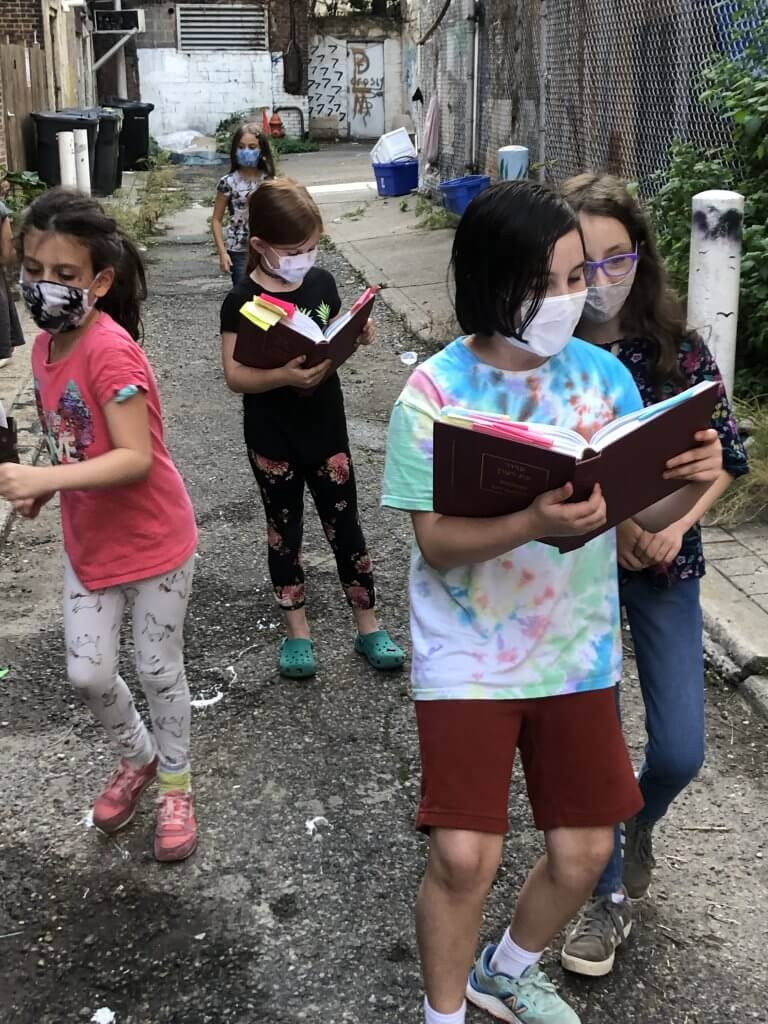

Commentary was the name of the game last week in our learning at Makom Community. Unsurprisingly, our inquisitive students have many of the same questions as some pretty big deal medieval rabbis. We unpacked the answers that some of those rabbis had to the questions and added our own insights.

One story that we discussed was from 15th century Torah commentator Bartenura. He expounded on the idea that Moshe’s brother Aharon was a lover and pursuer of peace. Upon noticing two people in conflict, Aharon would approach each party individually, and explain that the other felt terrible for fighting and wanted to make up. When the two people in conflict would meet again, they would kiss and embrace rather than continue to fight.

Garinim (preK and K kiddos) and Shorashim (1st and 2nd graders) had a lot of mixed feelings about this story:

- It solves the problem but it’s against one of the Ten Commandments to not lie.

- I agree – I think it isn’t good to lie, but in a way it’s helpful.

- This doesn’t solve the fight.

- We don’t know whether or not he was lying. Maybe both people really did feel sorry, even though they didn’t actually say it themselves.

- Maybe it wasn’t helpful at all. Maybe when the two people talked to each other again, they would realize that Aharon had lied, and that would make them even angrier and fight even more.

Is it always the best choice to just be honest? The Garinim imagined some examples of being only honest, only kind, only helpful, and a variety of combinations of those three things. We imagined several scenarios where being at least two of the three seemed good, but only one, maybe not so much:

- Only honest: someone looks at my drawing and tells me it’s ugly and weird.

- This one is just mean!

- Helpful and honest: someone tells me they don’t like my shirt, but suggests another one that looks better on me.

- Kind and helpful: in my class at school there are jobs that different kids do each day. If the kid with a certain job is out for some reason, when the teacher asks who’s supposed to do that job, I might say it’s me even though it’s not.

- Honest and kind: if I ask if I look better in a blue shirt or a red shirt and my friend just answers that they like the color red. Like saying a true and kind thing that doesn’t answer the question I actually asked.

The Shorashim also had pretty mixed responses about how they would feel in a situation of someone lying to help them resolve a fight. They rated how good they would feel on a scale from 0-100%.

- Why would they not be friends? If I get in a fight I wouldn’t not be their friend. I would try playing with them and play with my friends to try to make them feel better.

- 80% because maybe I would feel better because I thought that he was sorry. At least we are able to be friends in the end bit. I really don’t like the fact that he lied. Cause you can choose different ones not just thumbs down thumbs up or in the middle you can do other things

- 10% – nobody should ever lie.

- 50% – it depends on what happens. If you ask your friend and they don’t apologize, it could make the problem worse. Lying makes the problem worse.

They also had some good suggestions for what else you might do in a situation to fix conflict.

- If there is physical fighting you should tell the teacher.

- Someone might go in the mitbach shalom (“peace kitchen” the Shorashim calm down space at Makom Community) to calm down.

- We should calm down as well (take space from the other person).

The second commentary we unpacked was about honor and what it means to honor someone. In the story, Yaakov listens to what Rivkah tells him to do, even though he’s hurting someone else – his brother – in the process. One of the Ten Commandments is to honor your parents. From a certain perspective, we could think that Yaakov was following this commandment closely because he followed Rivkah’s instructions.

The Garinim unpacked what it means or looks like to honor or respect someone:

- Respect their questions

- Don’t bite them on the shin

- Do what they want or tell you to do

- Be kind

- Don’t hit them

The Garinim and Nitzanim (3rd and 4th graders) wondered why the Torah tells us specifically to honor our parents. Why not other members of our family or our friends?

- Without your parents you wouldn’t be alive.

- They provide you with resources to help you stay alive.

- They take care of you, they feed you, they give you shelter.

- As long as you’ve known them, they’ve loved you.

- We should also respect everyone else, but our parents are the closest, forever people in our lives.

Honoring and respecting our parents can be a tricky thing. Is it possible to do something that honors one parent but disrespects the other? Do Yaakov and Eisav do this? Do they manage to honor both of their parents?

- Yaakov honors Rivkah and Eisav honors Yitzchak.

- They honor their parents a little too much. Yaakov shouldn’t listen to his mom if she’s telling him to do something bad.

- They aren’t honoring their parents, they’re honoring their parent.

- The kids should be honoring both of their parents, and the parents should be honoring both of their kids.

- Yes, Eisav honors Yitzchak. He goes hunting when Yitzchak tells him to.

- No, Yaakov doesn’t say please when he wants the birthright. That’s not respectful.

In the end, these commentaries might have left us with more questions than answers. What do we do if, in trying to honor one person or one request, we might end up hurting someone else? Are there situations when a certain kind of lie might be more helpful than a full truth? And how do we navigate these questions as we try to resolve our own conflicts peacefully and productively? Stay tuned as we continue to explore!