“What is a criminal?” I asked the class.

“Someone who’s in prison,” Nathan said. “Who a lot of people agree has done something bad.”

“I don’t know if I agree,” Zoey said. “There are a lot of people in prison who haven’t done anything wrong. I don’t think you can just say that because they’re in prison that makes them a criminal.”

There were a lot of these moments of careful consideration during our study of Torah and racial justice: some disagreement and even some people changing their minds!

We started by defining what we were working towards: becoming tzadikim (righteous people) antiracists (people who acknowledge and actively fight racism). Watching Ibram X. Kendi speak on antiracism taught us that racism and antiracism are based in our actions, not our identities. We discussed how racism can be overt (obvious), covert (hidden/sneaky), and systemic (built into the ways the world works). While it can be scary to fight overt racism, it’s also the easiest to see and understand. A lot of the work we did in class involved trying to uncover and understand examples of covert systemic racism. We discussed what our strategies would be if we saw racist harassment happening at school, using the 5 D’s of Bystander Intervention. Leo said he would take the Direct approach, calling the person out on what they were saying, and then Delegate by telling an adult what happened.

The first piece of covert racism we tackled: segregation in schools. Segregation is a great example of a community (America) not living up to its stated values. We looked at how the Declaration of Independence’s rallying cry: “that all men are created equal,” isn’t reflected in the history of segregation. The same can sometimes be true in our Jewish texts as well. The bloody story of God punishing wayward Israelites by ordering them to be impaled (Bamidbar 25) doesn’t seem to hold up to the B’reisheet’s declaration that people were made in the image of God (B’reisheet 1:27). We discussed our own personal golden rules, when we’ve lived up to them and when we haven’t. Zoey noticed that it’s easier to follow her golden rule of being compassionate and supporting others when interacting with her friends and harder when interacting with family.

Keeping in mind that people and institutions sometimes don’t live up to their values, we looked at statistics around segregation in Philly schools. Everyone was shocked to learn that New York state has the most segregated school system in the country (most of the cohort guessed Alabama). One specific way that school segregation furthers inequality is through unequal funding. In Pennsylvania, state-based aid for students is very uneven due to a policy that stopped counting the students in each district in 1991. Districts that grew in population (mostly in cities where people of color live) got fewer dollars per student than shrinking rural and suburban school districts. Nathan stated what we were all thinking: “they should start counting again!”

From segregation, we looked at mass incarceration. Why does the United States have the highest prison rates in the world? We studied what the Rabbis had to say about sending people to prison from biblical times to today. It came back to b’tzelem elohim. If we’re made in the image of God, how can we put each other in prison?

“It’s like putting God in prison,” Nathan said.

We read through the introduction to Race to Incarcerate: A Graphic Retelling, which taught us about the history of prisons and the seriousness of our current problem. When we finished reading, I asked everyone if their thoughts on prisons had changed at all. Nathan said his definition of a criminal had changed, that he no longer believed that someone who is in prison is automatically a criminal. It’s so rare to see anyone change their mind these days, so I was very proud that Nathan felt comfortable sharing!

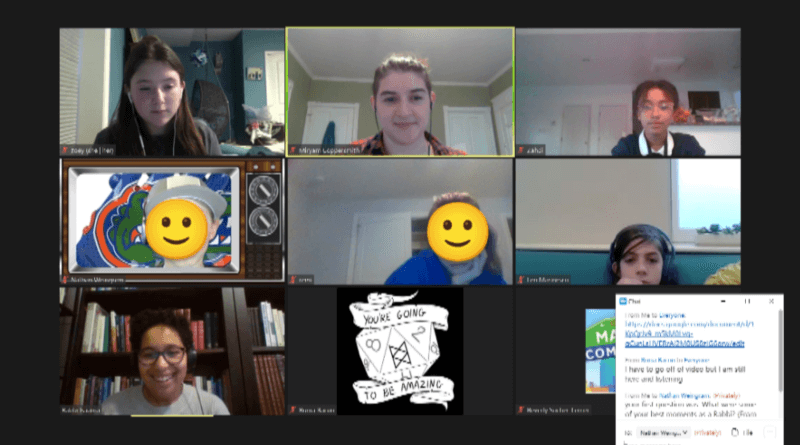

We capped this full week by having a guest speaker, Rabbi Isaama Goldstein-Stoll! The cohort asked her deep questions about being a Rabbi, how she fights for social justice, and how being a woman of color has affected her experience in the Jewish community.

“How does it feel to be part of such a small group, POC Rabbis?” Zahdi asked.

“It can be a lonely and isolating experience,” Rabbi Isaama said, though she noted that a lot of POC Rabbis know each other and can support each other. “When I try and push my fellow Jews to improve, it becomes a thing of power.”

She talked about hurtful moments when other Jews assumed her family was working at a synagogue and not there to pray as Jews, or when she’s been stopped by police tasked with protecting the synagogue. Ronia asked how she learns from Torah without rejecting it when she finds racist or sexist things in it.

“The cool thing is that for thousands of years, people have been wrestling with Torah, they don’t always come to the same conclusions,” Rabbi Isaama said. “That’s a positive affirmation that I have authority to read Torah.”

Zoey asked, “How can white jews help jews of color fight racism?”

“The best thing white Jews can do is to look at themselves and acknowledge their privilege…A lot of that comes from looking inward, seeing the bad thoughts, and recognizing it’s not our fault. Everyone has to do this work.”

With all this deep conversation, we ended by asking the rabbi how she stays hopeful and positive.

“My name, Isaama, is the name of my great-great-grandmother, she was the first person in my family who grew up out of slavery. My life is so much not the life of someone who’s a slave. I’m a black woman who’s gone to college, can read, became a Rabbi, is married to another woman. It’s easy to discount but there’s a lot of progress that has happened.”

I hope learning about that progress from Rabbi Isaama and our studies together as a cohort has allowed us to gain strength to fight the injustice we see in the world. I can’t wait to learn the Torah of this group’s fight for social justice as it evolves through our studies, conversations, and actions.